What makes a biodiversity hotspot?

Close your eyes and picture a biodiversity hotspot.

Imagine a place where thousands of species of weird and wonderful plants, from tiny, intricate mosses of every imaginable shape and color to the tallest trees on the planet and everything in between grow in a vast, diverse mosaic. Imagine hundreds of species of colorful, unique birds, both resident species found nowhere else in the world and migrants flocking from thousands of miles afield, making every inch of this verdant landscape their home.

What comes to mind? A lush, impenetrable tropical rainforest, perhaps? Maybe a dynamic African savannah?

Such ecosystems certainly are biodiversity hotspots, but if you live in California, you don’t have to imagine the landscape I mentioned - you’re right in the middle of it! And chances are, with a few easy steps, you may be able to play a pivotal role in saving it.

To be classified as a biodiversity hotspot, an ecosystem must meet two strict criteria - firstly, it must harbor at least 1,500 endemic plant species - in other words, plants found nowhere else on Earth; and secondly, more than 70% of it needs to be gone. This second criterion may sound odd, but it exists for a good reason - the current iteration of the biodiversity hotspot concept was formulated by a group of conservation biologists in 2000 with the purpose of prioritizing conservation work. The aim is to identify areas that are both incredibly important for sustaining global biodiversity and incredibly likely to disappear - habitats that are in the direst need of all-too-scarce conservation resources.

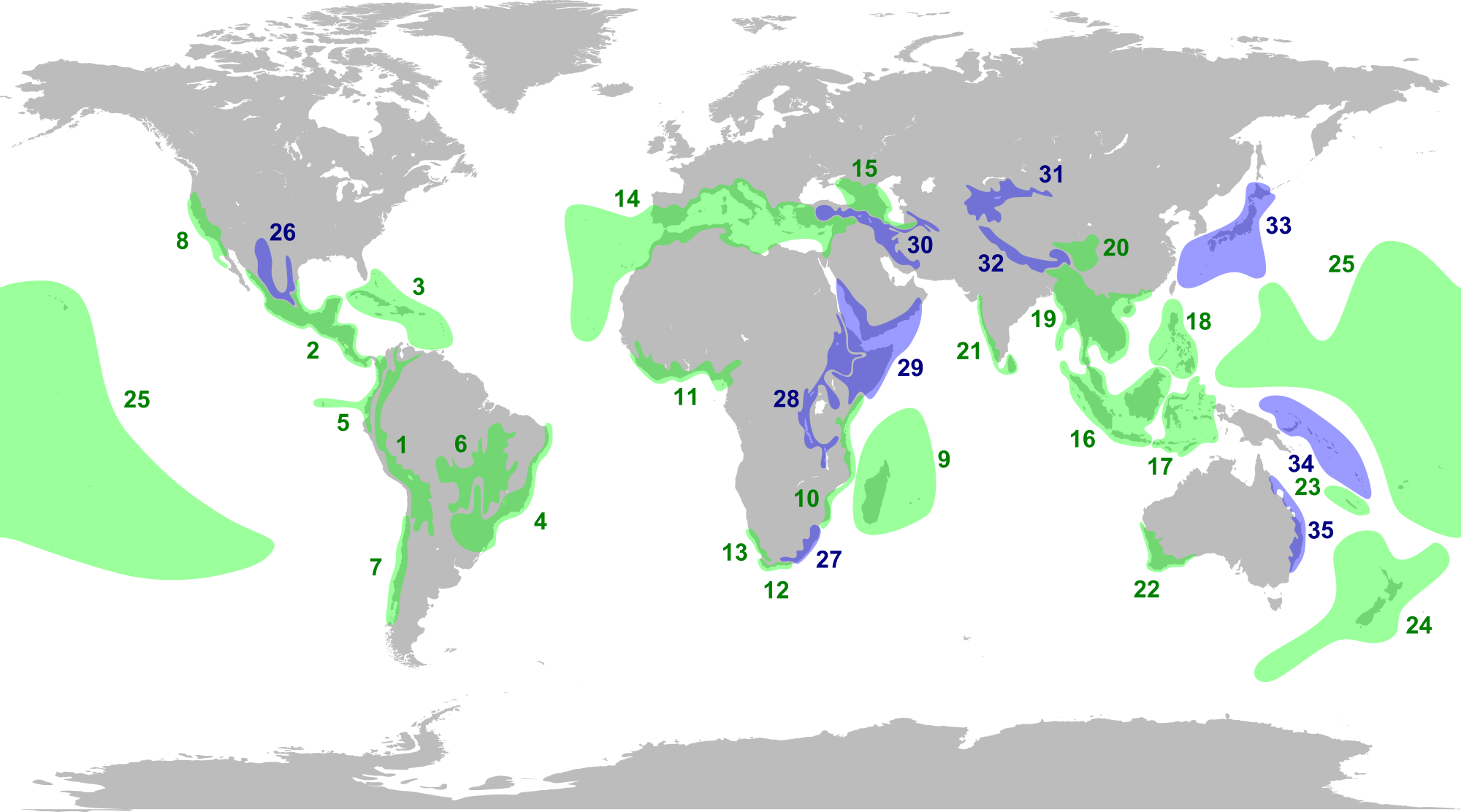

A map of biodiversity hotspots worldwide. (Phirosiberia on Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Biodiversity hotspots practically blanket the tropics - not only do most countries in the global South lack the regulatory infrastructure necessary to protect ecosystems from the externalities of the current explosion in development, but ecosystems close to the Equator are extremely localized, with a plethora of endemic species native to extremely small areas, often confined to a single mountain or valley. On the other hand, biodiversity hotspots are quite rare in temperate areas - not due to a lack of conservation issues, but simply due to the fact that ecosystems are less localized, translating to much lower rates of local endemism - for instance, the plant and bird species composition of the North American boreal forest, stretching from Newfoundland in the east to Alaska in the west, is largely uniform.

A map of regions with a Mediterranean climate. (Ali Zifan on Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

But there is a key exception to this general rule of temperate uniformity - the Mediterranean exception. A Mediterranean-type climate is characterized by warm summers, mild winters, and modest amounts of winter precipitation - more than a desert, but less than a forest. This type of climate is incredibly rare worldwide - there are only eight tiny pockets of land on the planet with a Mediterranean-type climate, and only five of them are found along the coast, where the water ensures climatic moderation throughout the year. There’s the Mediterranean basin of southern Europe and the Levant, the Western Cape province of South Africa, the southwestern corner of Australia, the central coast of Chile, and the California Floristic Province, which stretches from southwestern Oregon in the north to northern Baja California in the south. Remarkably, all five of these areas have three things in common apart from their climate - firstly, they all feature shrublands as one of their dominant habitats; secondly, they all are major centers of human population, and thirdly, they’re all biodiversity hotspots.